This investigation was a joint collaboration between The New York Times and The Wire China.

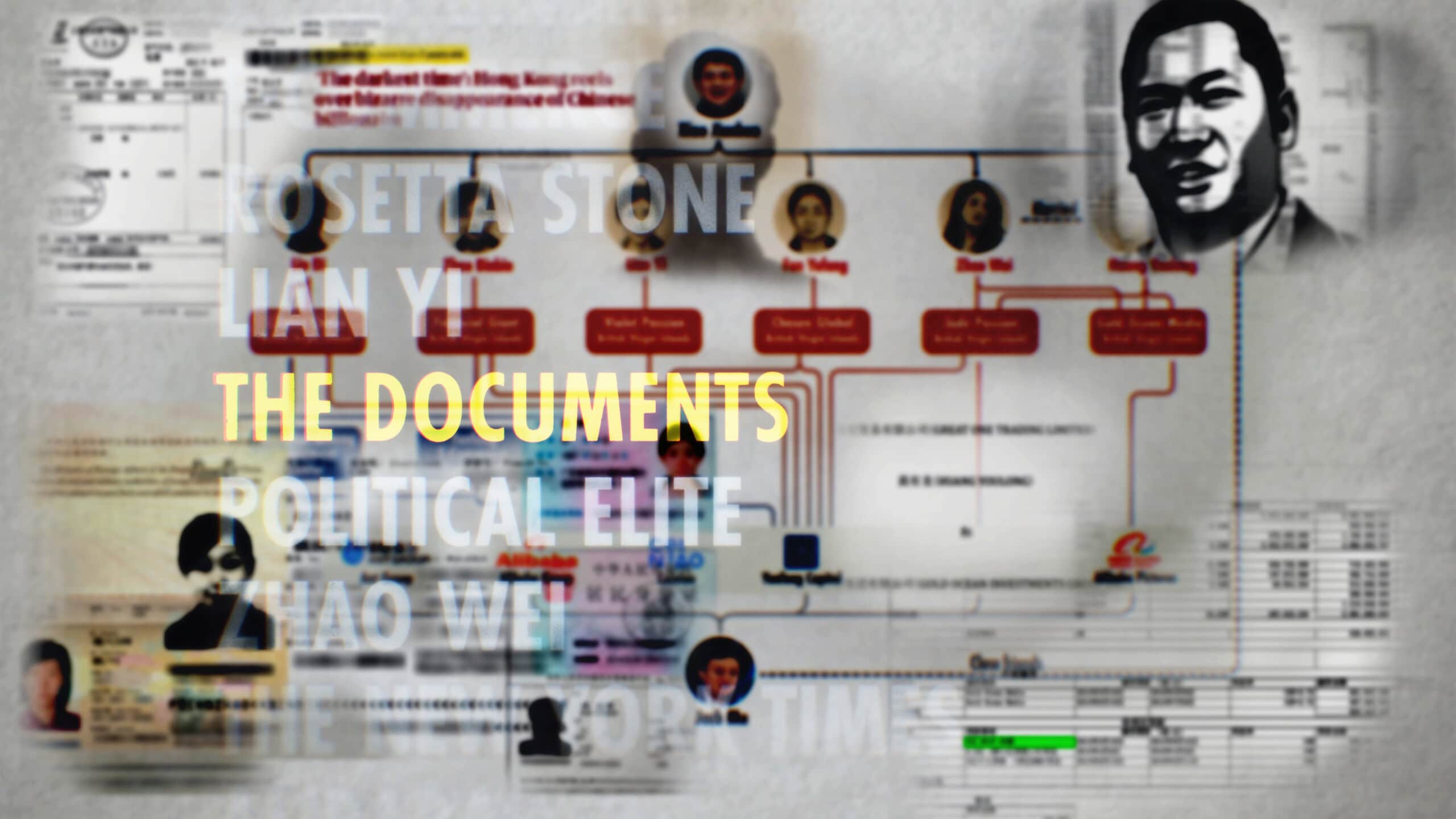

Four years ago, Jack Ma was the embodiment of China’s spectacular economic rise. Already the country’s wealthiest and most famous businessman, he was poised to become one of the richest in the world.

The expected initial public offering of Mr. Ma’s fintech company, Ant Group, was projected to surpass the record-shattering launch of his e-commerce giant, Alibaba. Soon, it was thought, he would be lionized like Bill Gates and Steve Jobs — a paragon of Western-style business in China.

At the same time, another wealthy Chinese businessman was awaiting a very different fate. Xiao Jianhua was languishing in detention on bribery and corruption charges — a larger-than-life target of a government crackdown on graft. Mr. Xiao had amassed a fortune manipulating markets and cultivating close ties to relatives of top Chinese officials, and he was about to be made an example.

And yet behind the scenes, these bookends of China’s catch-as-catch-can capitalism — its most celebrated and its most notorious billionaires — were linked through investments worth at least $1 billion, an investigation by The New York Times and The Wire China found.

A review of more than 2,000 confidential documents shows that Mr. Xiao’s now dismantled company Tomorrow Group secretly secured lucrative shares in an array of Mr. Ma’s companies over a period of five years. These business associations were never disclosed, and a former senior executive at Tomorrow Group said, “As far as we know, Jack Ma was unaware” of them.

The deals offer a close-up view of China’s signature brand of capitalism, where well-connected entrepreneurs and those who raise money for them are better off, at least in some cases, not interacting with one another. In almost any other robust economy, the proprietor of a major business would want to develop a relationship with an investor who raised $1 billion, and the investor would want to influence how the money was used.

Not in the China of Mr. Xiao and Mr. Ma.

The documents do not show that Mr. Ma knew about the Xiao investments, and speaking through a lawyer for Alibaba, Mr. Ma said he “never had any business relationship with Mr. Xiao.” The lawyer for Alibaba, in a statement, also said, “As far as Alibaba and its affiliates know, the connections you claim to exist do not have any basis in fact.”

But in one instance involving an Alibaba affiliate, the investigation found, Mr. Ma’s friend and business partner, Huang Youlong, entered into the investment on behalf of Mr. Xiao’s companies. In another deal involving a Hong Kong brokerage firm named in part after Mr. Ma, Mr. Huang and other Xiao associates were the biggest shareholders.

As late as 2020, even as Mr. Xiao sat in detention and Ant was preparing its I.P.O., companies and people in Mr. Xiao’s network held Ant shares with an estimated value of more than $300 million, the investigation found. In a surprise last-minute move, Chinese regulators halted the offering and launched investigations into both Alibaba and Ant, which to this day remains privately held.

The documents reveal the inner workings of the Xiao network, which he controlled through proxy shareholders that granted him anonymity and made the transactions difficult to decipher. They were concealed behind offshore entities and tracked on spreadsheets by Mr. Xiao’s staff. The Times and The Wire China were able to confirm transaction details through an examination of corporate filings and interviews, and two former employees of Tomorrow Group confirmed the authenticity of the documents.

Mr. Xiao’s specialty was helping influential officials and their relatives transfer wealth abroad and buy and sell assets; in at least one case, he did so for one of President Xi Jinping’s sisters. At his trial, the Chinese authorities suggested his holdings, which stretched from banking and insurance to rare metals, coal and real estate, were so vast that they threatened the country’s financial stability.

The documents also tell a story at times sharply at odds with the public narrative about Mr. Ma, who publicly derided the cronyism that pervades Chinese companies. That Mr. Xiao was able to benefit from Mr. Ma’s world, even as some of New York’s most prestigious law firms conducted due diligence on the deals, was shocking — and telling — to scholars of China’s economy.

“Finding them connected this way,” said Meg Rithmire, a Harvard Business School professor who has studied Mr. Xiao’s financial network, “shows that the Chinese system is so murky that everyone gets caught in the same web.”

Mr. Xiao is now serving a 13-year sentence, and Mr. Ma has all but retreated from public life, having no formal role in the companies he founded. Both men — one defrocked, the other locked away — are among the highest-profile targets in Mr. Xi’s dramatic consolidation of power since he became China’s top leader over a decade ago.

At the time, Alibaba and Jack Ma were so successful. Everyone wanted to invest with them. They had the magic touch.

A former senior executive at Tomorrow Group

Mr. Ma’s clashes with the government have been well documented, including his running afoul of Mr. Xi for criticizing the push for stronger financial oversight of his companies. But until now, nothing has been publicly known about the investments linked to Mr. Xiao.

The Times obtained the documents in 2018, more than a year after Mr. Xiao was abducted in Hong Kong and spirited into mainland China, and they have been used in various reporting efforts. In parts English and Chinese, they include brokerage and bank statements, contracts, corporate registration filings and spreadsheets mostly from the company’s Hong Kong operations.

Looking for the best China coverage?

Subscribe to The Wire China today.

The source of the material, who once worked for Tomorrow Group, wanted to expose how Mr. Xiao secretly controlled and manipulated companies and how financial regulators in Hong Kong and China failed to stop him, the source said. Because Tomorrow Group was also under government investigation, it is possible that Chinese authorities have access to the same information, the source said. Mr. Xiao was praised for his cooperation at his sentencing.

The Times revisited the documents last year and shared them with The Wire China. Their joint investigation found that the investment connection between Mr. Ma, 59, and Mr. Xiao, 52, had begun several years before the 2017 abduction.

Mr. Xiao, who is in prison in Shanghai, could not be reached for comment. The former senior executive at Tomorrow Group confirmed that the company was behind the investments. “At the time, Alibaba and Jack Ma were so successful,” the former executive said. “Everyone wanted to invest with them. They had the magic touch.”

‘CLANDESTINE AND DISPERSED’

As China’s economy boomed in recent decades, many well-connected families earned billions of dollars by leveraging their clout over highly regulated industries.

Leading the charge were the so-called princelings — the relatives of top Communist Party officials — who controlled the intersection of state influence and private wealth. Their behind-the-scenes efforts could save or wreck deals, and they did so without worrying about being unmasked by the Chinese media or facing consequences on Election Day.

Mr. Xiao was their longtime concierge.

From the time he was a 17-year-old student leader at Peking University, Mr. Xiao began to develop ties to the country’s power structure. With a coterie of female bodyguards, at least two foreign passports and more than 100 offshore companies, he amassed riches through state-dominated industries rife with cronyism: banking, insurance and brokerages.

Mr. Ma was not part of this system. In the late 1980s, he took a job as an English teacher making $14 a month, and when he founded Alibaba a decade later, he followed the Silicon Valley playbook, acquiring funds from savvy global investors like Goldman Sachs and Japan’s SoftBank.

For Mr. Ma, Chinese officials were to be respected and obeyed but otherwise avoided. “I do everything they tell me,” he told an audience at Stanford University in September 2011. “But do business? Sorry.”

Jack Ma delivers a speech at the Stanford Graduate School of Business, September 30, 2011. Credit: Stanford Graduate School of Business

The Chinese authorities began paying more attention to Alibaba as its success took off. Mr. Ma has said he was pressured to transfer Alipay, a mobile payment system now controlled by Ant Group, to a Chinese company. Mr. Ma also moved to increase Chinese ownership in Alibaba, which at the time had more than 70 percent of its shares held by foreign investors.

It was around this time that Mr. Ma and Mr. Xiao’s parallel universes first converged.

The same month that Mr. Ma spoke at Stanford, Chinese investors began increasing their foothold in Alibaba. The select group included Mr. Ma’s friends as well as an obscure British Virgin Islands shell company called Financial Giant, which invested $25 million, the documents show.

On paper, Financial Giant’s owner was an unknown 24-year-old woman whose family hailed from a small city near the Russian border. Two Swiss banks — UBS and J. Safra Sarasin — lent her legitimacy by opening brokerage accounts for her company.

The woman, Zhao Binbin, could not be reached for comment. She had something else going for her, the Tomorrow Group documents show: She belonged to a family that acted as proxies for Mr. Xiao, and she was holding the Alibaba shares on his behalf.

One of her relatives, a piano teacher, was listed as the top official of a Xiao company that in 2013 bought assets from one of Mr. Xi’s sisters. The same relative was married to a Xiao employee who in 2014 bought a $62 million Van Gogh painting at a Sotheby’s auction.

“When Boss Xiao was building Tomorrow Group, there was a saying: ‘clandestine and dispersed,’” said the former Xiao employee who provided the documents, speaking on the condition of anonymity because the former employee still works in the industry.

“Xiao’s name and Tomorrow’s name will not appear,” the former employee said.

PLAYING THE PRINCELINGS GAME

It is unclear how or why Mr. Ma and Mr. Xiao first became acquainted. They met in Beijing in 2013, at a club affiliated with a major Chinese bank, one person close to Mr. Xiao said. An undated photo surfaced on a Chinese social media site in 2018 showing them toasting each other at a restaurant with kimono-clad servers.

The “why” behind the Xiao investments may have more to do with China’s inescapable world of princelings than any pressing business imperative. As relatives of China’s political elite looked to benefit from the country’s growing economy, Mr. Xiao made a career of connecting them with promising ventures — and often concealing those connections behind shell companies, proxy investors and other smoke screens.

In 2010, Mr. Ma co-founded an investment firm, Yunfeng Capital, and investors got early access to his companies. One of Mr. Xiao’s proxies, the young woman from near the Russian border, was among them, acquiring her Alibaba shares through Yunfeng around 2011, the investigation found.

By the following year, in anticipation of Alibaba’s I.P.O., Mr. Ma was looking to pare down foreign ownership in the company — particularly Yahoo’s huge stake — and brought in a new corps of Chinese investors. A $7.6 billion deal to buy back about half of Yahoo’s holdings was financed in large part by Chinese banks and investment firms led by princelings, including Boyu Capital, which was founded by the Harvard-educated grandson of a former Chinese president, Jiang Zemin.

By 2014, Mr. Ma had become a money-making machine for the country’s political elite. Chinese firms owned or overseen by relatives of six current or former Politburo members had invested in Alibaba and its affiliates, according to company records.

In a statement on behalf of the companies, Alibaba described the investors as “reputable state-owned firms or well-regarded private investment firms,” adding that it had “never solicited investments from any investor on account of their ‘political connections.’”

The most lucrative event was Alibaba’s I.P.O. on Sept. 19, 2014, when the e-commerce giant’s market value shot past that of its biggest rival, Amazon. Mr. Xiao’s $25 million investment, made through his proxy, soared to $160 million that day.

It was a heady day for Mr. Ma at the New York Stock Exchange, which was decked out in Alibaba orange. Beaming before the cameras, he posed with friends and colleagues, including a stocky man who appeared fleetingly in a video produced by Alibaba documenting the I.P.O.

Huang Youlong shows up several times in a video documenting Alibaba’s September 2014 I.P.O.. Credit: Alibaba Group via YouTube

The man was Huang Youlong, a businessman married to one of China’s most famous actresses. He was also Mr. Xiao’s ticket to even bigger stakes in Mr. Ma’s companies, The Times and The Wire China found.

THE MOVIE STAR’S HUSBAND

Mr. Huang, 47, stands out from the rest of Mr. Ma’s high-achieving friends: He didn’t look the part, and he lived a bit of a charmed life.

He became a citizen of Singapore and went into business there with an American who was later jailed in the United States for illegally exporting aviation equipment to Iran. He became a business partner of a Chinese casino magnate who is now reportedly a fugitive. And in 2008, he married Zhao Wei, a famous Chinese actress who would eventually fall from favor and be mysteriously erased, film credits and all, from the Chinese internet.

By 2014, Mr. Ma and Mr. Huang had become close. In a sign of friendship, Mr. Ma joined Mr. Huang that year at his father’s 80th birthday party and even sang at the celebration, Chinese media reported.

When it came to his own businesses, Mr. Ma was joined by Mr. Huang in blockbuster deals, the Tomorrow Group documents show, in which Mr. Huang both acted as a proxy for Mr. Xiao and sought to profit for himself.

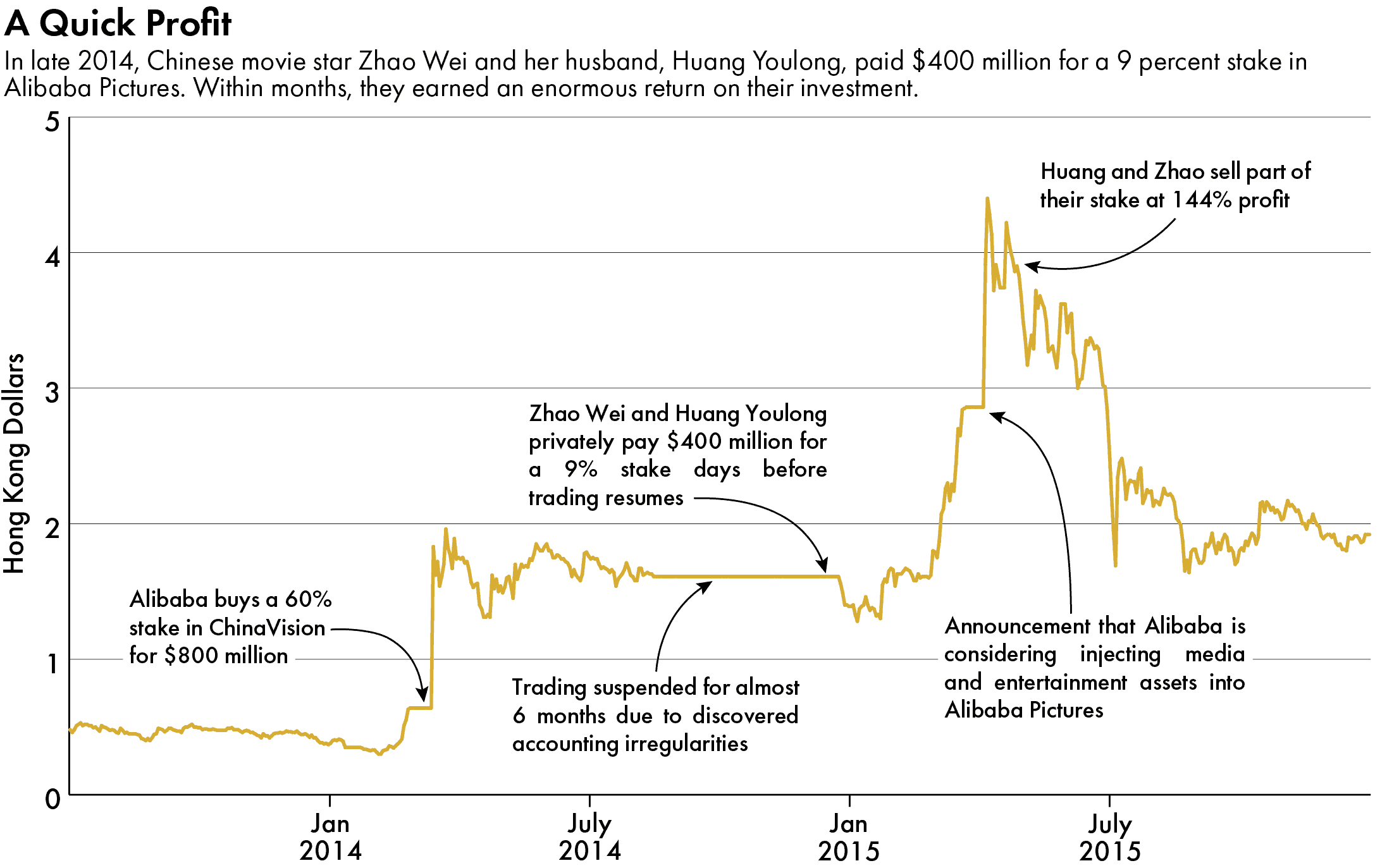

In 2014, Alibaba bought ChinaVision, a film and television production company, and renamed it Alibaba Pictures. But the purchase immediately ran into problems when accounting irregularities were discovered in the former company’s books.

Trading in Alibaba Pictures stock was temporarily suspended, and two days before it resumed, Mr. Huang and his wife paid about $400 million to acquire a 9 percent stake from ChinaVision’s former chairman. The widely publicized investment boosted confidence in the new company, in part because Ms. Zhao was a bankable movie star at the time.

But the couple paid for it with money from one of Mr. Xiao’s companies, the documents show, a fact not publicly known and not included in disclosures to the Hong Kong Stock Exchange.

The documents reveal that the Xiao company financed 60 percent of the purchase and privately lent Mr. Huang $125 million at 8 percent interest to pay for the majority of the couple’s 40 percent stake. Mr. Huang also received a $75 million loan from Credit Suisse to help pay for the shares. While the loan was in Mr. Huang’s name, Mr. Xiao’s team handled payments and correspondence with the bank, the documents show.

China watchers rely on The Wire China.

Get unlimited access today.

Mr. Huang did not respond to emails or questions sent to his Hong Kong office. In a statement, Alibaba said it was “not involved in the transaction, and had no knowledge about Mr. Huang and Ms. Zhao’s investment activities,” though it acknowledged it had consented to the transaction.

The investment quickly paid off. In April 2015, shares in Alibaba Pictures soared as Alibaba said it was considering injecting some of its own entertainment assets into the company. Days later, Mr. Huang sold some of his holdings, netting a $75 million profit, or a return of 144 percent in four months. A near-identical amount was paid to Mr. Xiao’s company, the documents show.

‘JACK’S EYES AND EARS’

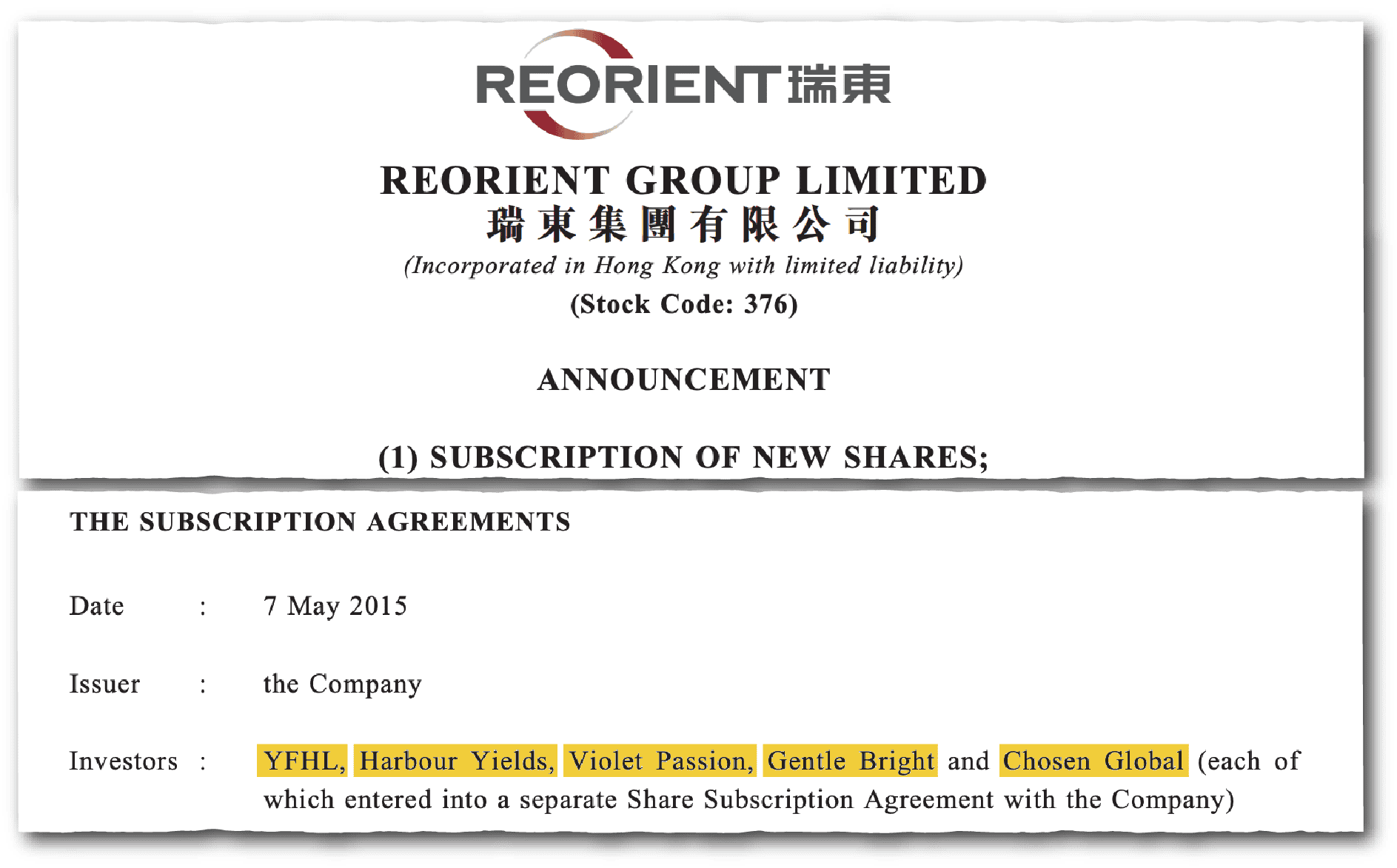

By the time Mr. Huang cashed out those holdings in Alibaba Pictures, Mr. Ma’s investment firm had already set its sights on a new business: Reorient Group, a Hong Kong brokerage run by a business partner of Erik Prince, the American security contractor.

Taking over Reorient would give Mr. Ma and David Yu, a friend and Shanghai financier who was his partner on the deal, a foothold in Hong Kong’s financial sector. They would rename the company Yunfeng Financial after the firm they founded earlier, Yunfeng Capital.

“This is a strategic investment for us,” Mr. Yu said at the time.

Mr. Ma owns 40 percent of Yunfeng Capital and remains closely associated with it. (The “Yun” in Yunfeng is Mr. Ma’s given name in Chinese.) He took the stage in Beijing when they debuted the company in 2010 and Yunfeng Capital later joined Alibaba on at least a half-dozen deals.

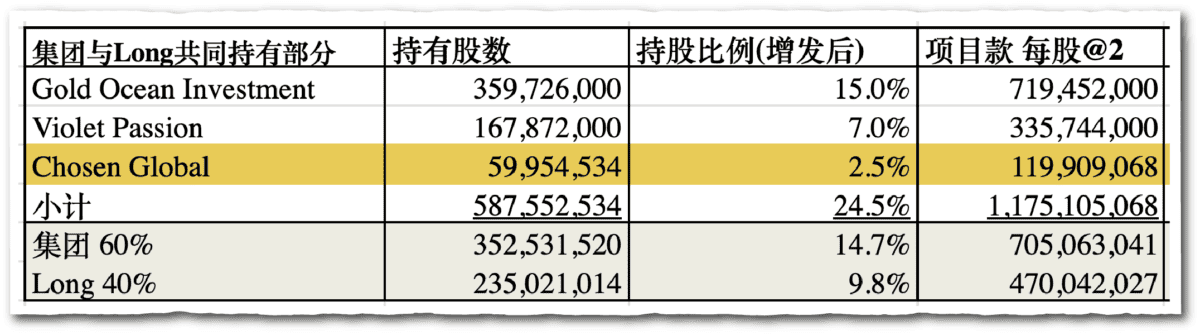

The Reorient purchase is the clearest evidence that Mr. Xiao was a crucial shareholder in one of Mr. Ma’s companies. Through four offshore companies and a fifth firm owned by Mr. Huang, Mr. Xiao controlled roughly one-third of the company’s shares by the end of 2015, making his network the largest shareholder — even larger than Mr. Ma.

When Boss Xiao was building Tomorrow Group, there was a saying: ‘clandestine and dispersed.’ Xiao’s name and Tomorrow’s name will not appear.

a former Xiao employee who provided the documents

The deal took weeks to negotiate, and both Mr. Huang and his wife were a regular presence in the talks, recalled one former senior Reorient executive who was not authorized to speak publicly about the deal. Mr. Huang acted as “Jack’s eyes and ears,” the executive said.

The purchase followed a familiar playbook from Alibaba Pictures and other deals. Reorient’s top executives sold a controlling stake to Mr. Ma and his fellow investors, issuing them new shares at a steep discount, according to a regulatory filing. When news broke that a firm co-founded by Mr. Ma had made the investment, Reorient’s shares soared more than 150 percent.

In a statement, Yunfeng played down Mr. Ma’s role in the firm, saying he “is not involved in the decision-making or operation.” But the former senior executive at Tomorrow Group said Mr. Ma was the main attraction. “When we had a chance to invest in his companies,” the executive said, “we often did this through Huang Youlong or Yunfeng Capital.”

Mr. Xiao’s network paid a premium to become the biggest shareholder, the documents show, offering a glimpse into the shadow world of Hong Kong finance, where side agreements often spell out ownership of shell companies.

A contract between Mr. Huang and a company controlled by Mr. Xiao showed that they had to pay a $190 million premium to an unspecified beneficiary, effectively doubling the price of their investment.

On paper, Mr. Huang retained a 10 percent stake himself, but a spreadsheet shows that even that holding was obtained with loans from Mr. Xiao’s company.

At the time, the filing with regulators said nothing about Mr. Xiao, who, the documents show, actually invested alongside Mr. Ma in Reorient through three separate companies. Two of them were owned by stand-ins for Mr. Xiao, including a 27-year-old woman from the Inner Mongolian city where Tomorrow Group once operated.

In separate statements, Mr. Ma, Yunfeng and Johnson Ko, the chairman of Reorient at the time, said they had no knowledge of the Xiao connection. “Reorient conducted thorough know-your-clients due diligence,” Mr. Ko said.

Weeks after the deal was finalized, the ex-wife of Mr. Ma’s business partner, Mr. Yu, benefited enormously from Mr. Xiao’s continued interest in Yunfeng Financial. Two offshore entities controlled by Mr. Xiao paid $235 million to buy an additional stake in the company from the ex-wife.

She netted a windfall of more than $190 million, public records show. In its statement, Yunfeng Capital described her as “an independent investor.”

A CAMPAIGN AGAINST GRAFT

In 2017, the dragnet of Mr. Xi’s corruption crackdown finally closed in on Mr. Xiao.

Years earlier, in his first speech to the Politburo as Communist Party chief, Mr. Xi made clear that the party was facing an existential crisis after six decades of rule.

Stay on top of China news.

Join the thousands of policymakers and business leaders who rely on The Wire China.

“A mass of facts tells us that if corruption becomes increasingly serious, it will inevitably doom the party and the state,” Mr. Xi said in November 2012.

Before the year was out, government officials were being rounded up in an ever-widening campaign against graft, which also took down some of Mr. Xi’s most powerful political rivals.

In March 2013, Mr. Xi became president, and that same year his relatives shed hundreds of millions of dollars in insider investments. In a statement to The Times in 2014, a spokeswoman for Mr. Xiao confirmed that the president’s sister and brother-in-law had finalized the sale of their 50 percent stake in a Beijing investment company they had set up in partnership with a state-owned bank. Their stake was sold to a company founded by Mr. Xiao.

The crackdown initially focused mainly on government and party officials and their relatives, not business leaders, but soon virtually no one was off limits. Mr. Xiao’s turn came under cover of night in January 2017, when he disappeared from his apartment at the Hong Kong Four Seasons Hotel.

Video footage captured by security cameras showed he was taken away in a wheelchair, his head covered, accompanied by about a half-dozen unidentified men pushing a large suitcase. It is believed he was then transported by boat from Hong Kong, eluding border controls, to police custody in mainland China.

In the days that followed, Mr. Xiao’s relatives and associates scrambled to unload some of their holdings, including more than $60 million held in a Yunfeng Capital fund, the Tomorrow Group documents show. The company that bought the stake was run by a business associate of Mr. Huang’s, Chinese corporate records show.

Mr. Xiao’s role as concierge to the Communist Party elite had come to an end. But his financial ties to Mr. Ma had not — just as Ant Group, the e-payments and personal lending company, had become Mr. Ma’s latest darling.

THE FINAL UNDOING

By 2018, Ant had more than 700 million active users, and the company was barreling its way toward an I.P.O..

Mr. Ma followed the old playbook in preparing for the offering, corralling a group of powerful political elites as investors, The Wall Street Journal reported in 2021.

Mr. Xiao was secreted away in detention. But members of his network controlled about a tenth of a percentage point of Ant’s shares, according to data from WireScreen, a sister company of The Wire China that compiles Chinese corporate ownership data. Even that small fraction would be worth about $307 million if the I.P.O., as had been expected, valued the company at more than $313 billion.

One Xiao employee, the corporate records show, was the single largest investor in a fund full of Mr. Ma’s friends and their relatives, including the mother of Ms. Zhao, the movie star. The fund was managed by Yunfeng Capital and was one of the largest holders of Ant shares.

Yunfeng and Ant said in statements that they were not aware of any connection between their investors and Mr. Xiao.

By the end of 2019, as the Chinese authorities were unwinding Mr. Xiao’s network of companies, they saw concerning parallels in Ant’s ownership structure, according to Angela Huyue Zhang, a law professor at the University of Hong Kong who recently wrote a book about China’s regulation of technology companies.

Like Mr. Xiao’s Tomorrow Group, Ant was dominated by a single person. And there were troublesome ripple effects of Mr. Xiao’s downfall. A bank he had controlled, Baoshang, filed for bankruptcy in 2020.

China’s central bank would need to intervene, Professor Zhang said, “if something bad happens to Ant like what happened to Baoshang.”

The authorities had drafted new rules that would rein in private financial systems, and Mr. Ma made their decision to intervene in Ant easier to justify during a speech in Shanghai.

Finding them connected this way shows that the Chinese system is so murky that everyone gets caught in the same web.

Meg Rithmire, a Harvard Business School professor

Mr. Ma took aim at China’s state-dominated banking system, arguing that it constrained innovation and growth through a “pawnshop mentality” by lending only to those who posted collateral. He roasted financial regulators for being obsessed with minimizing risk.

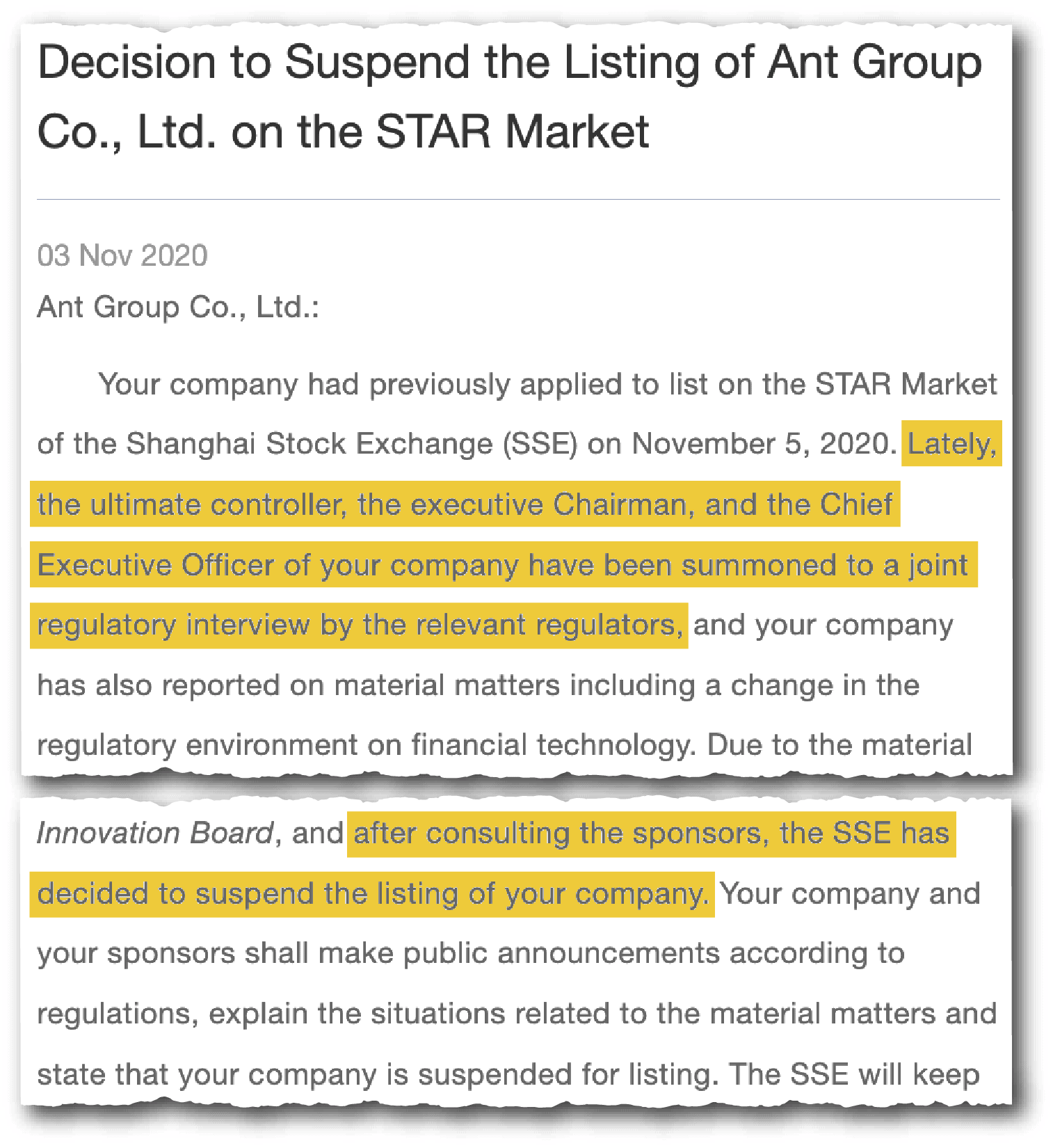

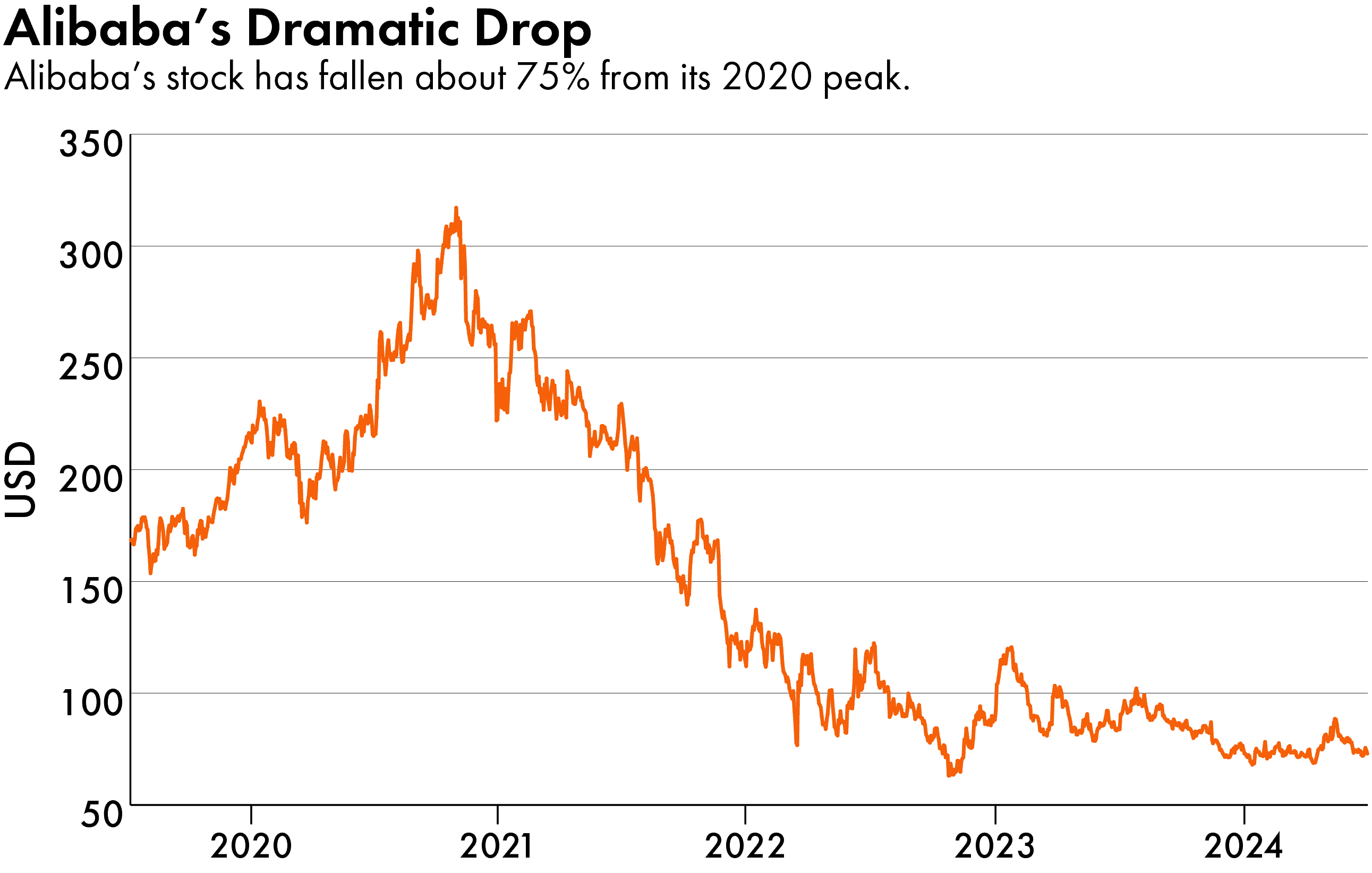

That was in October 2020. By early November, the Chinese government called off Ant’s I.P.O., the opening salvo in its assault on big tech. On social media, one post derided Mr. Ma’s remarks as “the most expensive speech in history.”

Since then, Mr. Ma and his companies have been routed. Alibaba’s stock is down about 75 percent from its peak. Mr. Ma’s voting power in Ant has been mostly stripped away. A turnaround strategy announced by Alibaba last year has languished. Plans to publicly list some of its assets have been put on ice.

Some of Mr. Ma’s friends haven’t fared any better. Mr. Huang was sued in Hong Kong for millions in unpaid debts. His wife, Ms. Zhao, has not appeared in a movie since 2019, though some references to her on the Chinese internet have been restored. Mr. Ma, in his statement, said he had not been in contact with either of them “for many years.”

Muyi Xiao contributed reporting.

Michael Forsythe is a reporter on the investigations team at The New York Times, based in New York. He has written extensively about, and from, China. @PekingMike

Katrina Northrop is a former staff writer at The Wire China, and joined The Washington Post in August 2024. Her work has been published in The New York Times, The Atlantic, The Providence Journal, and SupChina. In 2023, Katrina won the SOPA Award for Young Journalists for a “standout and impactful body of investigative work on China’s economic influence.” @NorthropKatrina

Eliot Chen is a Toronto-based staff writer at The Wire. Previously, he was a researcher at the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ Human Rights Initiative and MacroPolo. @eliotcxchen