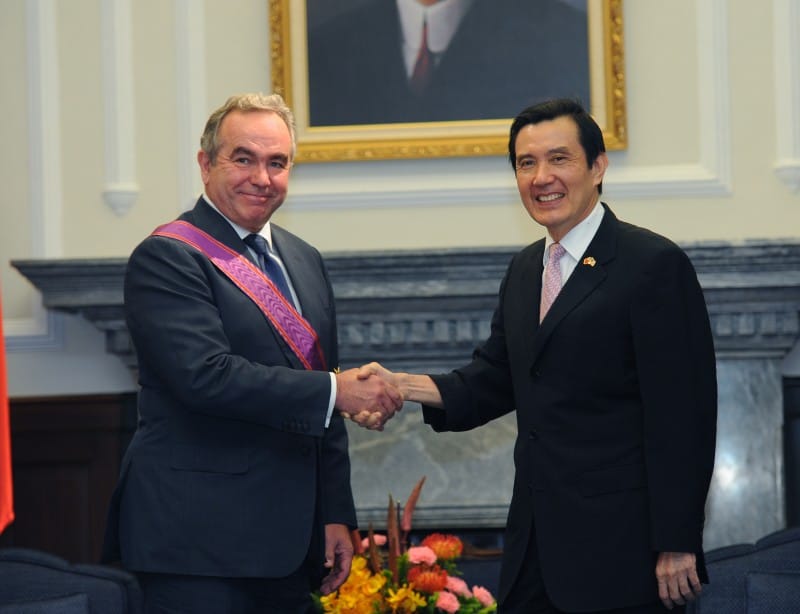

Kurt Campbell, the White House’s Asia chief, has played a significant role in developing U.S. policy toward China since the Clinton administration. The arc of his career mirrors the overall change in the relationship from engagement to competition. Under President Clinton, Campbell worked on Asia issues at the Pentagon and separately was part of a White House team advocating for the North American Free Trade Agreement. During the Obama administration, he was assistant Secretary of State for East Asian affairs and helped formulate the “pivot” to Asia, aimed at shifting America’s military and foreign policy focus to China and the rest of Asia. By 2018, he was writing in Foreign Affairs about the failure of engagement to remake China. Three years later, President Biden named him the National Security Council’s coordinator for the Indo-Pacific. There he has helped devise administration policy for competing with China. That includes putting together a submarine-building deal with Australia and Great Britain, called AUKUS, and developing a tighter relationship between the U.S. and India. Campbell is married to Lael Brainard, the director of the National Economic Council. She worked on China issues at the Treasury during the Obama administration.This interview is part of Rules of Engagement, a series by Bob Davis, who covered the U.S.-China relationship at The Wall Street Journal starting in the 1990s. In these interviews, Davis asks current and former U.S. officials and policymakers what went right, what went wrong and what comes next.

Illustration by Lauren Crow

Q: This is a very interesting time in U.S.-China relations. If we had talked during the balloon incident, we would have a different kind of conversation. Now you hear people talking about a thaw, a rapprochement or a reset. How would you characterize relations?

A: When talking about U.S.-China relations, it’s important to explain how we got here. When President Biden came to power, he asked his national security team for a very deep, intensive assessment of the state of U.S.-China relations that covered every aspect of our relationship. The assessment said that under President Xi, China had embarked on a very ambitious course. They believed that the United States was in a hurtling decline. They sought to aggressively move to accentuate that decline and to assume a much larger role in global politics. The sense was to challenge the United States in almost every quarter.

As we looked at economics, trade and other relations [we saw] that in almost every capacity China was seeking advantage, oftentimes to the detriment of American technology providers and business groups. We also heard from many of our allies and partners, in the region and elsewhere, a growing anxiety about Chinese activities.

By almost any measure, the last 40 or 50 years have been the best period in Asia’s long history, with enormous numbers of people raised out of poverty, wealth creation, and innovation across the board. A huge reason for that is the creation of a kind of operating system. It’s complex and nuanced and depends on a number of things, including peaceful resolution of disputes, management of complex issues in a legal manner and freedom of navigation buttressed by the American commitment to maintain peace and stability throughout Asia.

As a rising power, China sought to change elements of that system. That’s probably to be expected. But some of the changes they were seeking, we thought, would undermine that order in ways that would be very detrimental to us and our allies and partners.

So, the President laid out a multifaceted course. That began with the attempt to build a sense of bipartisanship inside the United States about the need to focus more intensively on the Indo-Pacific. There was also the recognition that some of our core capacities and technology, [including] on the military side, had hollowed out. There was going to be a need to substantially reinvest in those capacities.

There was also a recognition that for us to be effective we had to work more constructively and more effectively with allies and partners. What you’ve seen over the last two and a half years is unprecedented. There have been innovative, and also traditional approaches to building allies and partnerships.

Many would say, ‘Oh, gee, you’ve continued the Trump approach.’ But I would say that the big difference is that President Trump saw this as a narrow, bilateral issue, and distrusted allies and partners. He treated them quite poorly at times. We’ve sought to diversify, to do it differently.

Aren’t you leaving out a third part? I understand that the administration has been trying to build up the U.S. and work with allies. But isn’t the third part hobbling China?

I do not believe that there are any indications of that. If you look at last year, it was a banner year in trade — the largest year in trade between the United States and China. We think there are many areas of economic pursuits that are critical to both of our economies.

We have tried to identify a few key technologies where we believe it is critical for the United States to maintain leading-edge capabilities. We also believe that some of the steps China has taken to use these technologies in a military or security arena — like facial recognition, AI in the military, or innovations in hypersonics — are antithetical to our security interest. We have tried to make clear that there is a difference between a narrow derisking and a broad decoupling.

At the end of this effort, the idea is to begin consequential diplomacy with China with a sense that the United States is deeply committed to playing a role in the Indo-Pacific, and we are not leaving the global stage.

Obviously, the balloon interrupted some of that initial diplomacy. But I would say now we are back to seeking careful, productive, strategic interactions with China. There is a need to be able to deal with the consequences of actions, which through inadvertence or accident, require immediate communications.

| BIO AT A GLANCE | |

|---|---|

| AGE | 65 |

| BIRTHPLACE | Central San Joaquin Valley, California |

| CURRENT POSITION | Deputy Assistant to the President and National Security Council Coordinator for the Indo-Pacific |

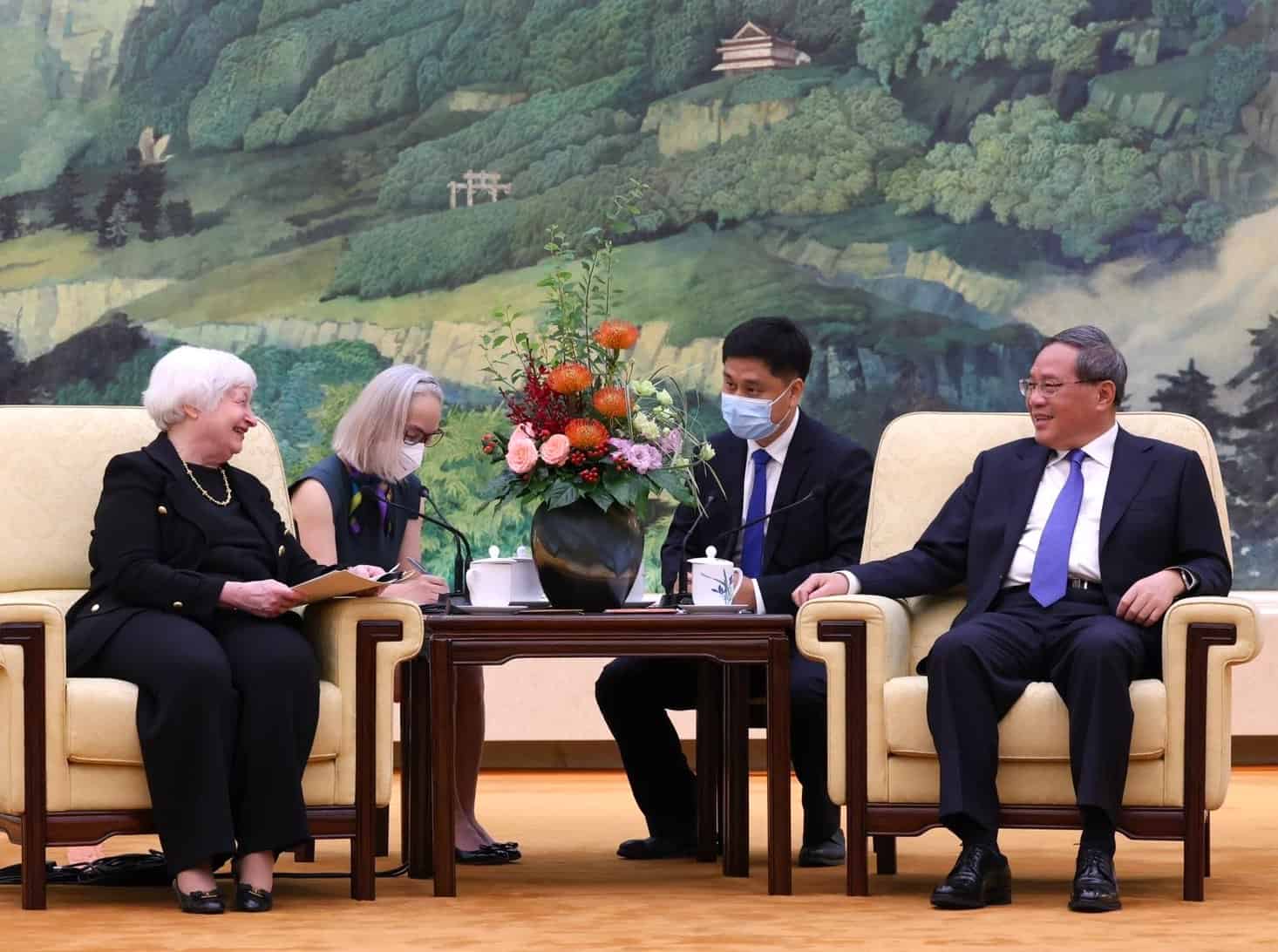

We’ve also seen in the last few days, with [Treasury] Secretary Yellen’s visit to Beijing, there is an important economic element to this [communication], not only in explaining the difference between a broad decoupling and a narrow derisking, but also in making clear that there are important discussions [needed] about larger macroeconomic trends, such as inflation and issues associated with international debt policy.

It wasn’t very long ago that China was arguing that ‘No, we’re not going to engage with the United States anymore.’ And suddenly, that changed a few months ago. In many of our discussions they raise quite prominently what we and our allies and partners are doing on technology policy. They are trying to influence some of what we’ve done.

To get you to reduce your effort?

Yes. But I would point out that the G7 document in Hiroshima was the most ambitious set of steps that allies and partners have taken on technology. And there was more of a joint vision on the Indo-Pacific than we’ve ever seen. China feels some of those things are probably effective, so they’ve tried to engage us to alter our course.

| BOOK CORNER | |

|---|---|

| I love Don De Lillo’s The Names, all the James Church mystery/spy novels about the North Korean Inspector O, especially Murder in the Koryo. I recently read (again) David Halberstam’s The Coldest Winter and Arther Koestler’s Darkness at Noon. I’m starting new biographies on Admiral Nimitz and President Eisenhower. |

|

It is also the case in China that effective management of U.S. relations is important. Perhaps President Xi and his senior team felt some concern that there were those in the system raising questions about that. It is also the case that the Chinese economy is slowing.

There are many in their system that understand that people are wary of the Chinese market — wary of what’s going on in terms of controls and actions inside China. They’re trying to signal, ‘Come on in, the water’s fine.’ It is also the case that they may see some areas where certain kinds of common engagement might make sense.

What are the areas where you think they are interested in engagement?

They appreciate issues associated with climate, although not at the highest level. I think [they are concerned about] the global economy. They have experienced earlier periods, like in 2008 and 2009, where the engagement between the United States and China was significant. [The U.S. and China worked closely together during the Global Financial Crisis to stimulate the global economy.]

They want to keep those lines of communication open. It is also the case that in all likelihood, later this year, President Xi and President Biden will have interactions. They want a greater degree of predictability and stability. [Asia specialists say President Biden and President Xi are expected to meet in San Francisco during a November summit of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum.]

| MISCELLANEA | |

|---|---|

| FAVORITE MUSIC | I enjoy all music but am unusually smitten by Irish balladeers and Celtic folk. It usually leads to tears. |

| FAVORITE FILM | I love all the Jason Bourne movies, Ronin, The Martian and The Godfather. A night at the movies is generally a good night. |

| MOST ADMIRED | My wife Lael Brainard is up there. Churchill, Marshall, Admiral William Crowe, Hedley Bull, and maybe Larry Bird. |

For all of those reasons, both countries are approaching this set of interactions carefully. We hear a long list of grievances in every interaction, but at the same time we believe we’re laying down markers about issues we think are important. This kind of diplomacy is effective.

I believe that we’ve entered a new period where results have more to do with clear lines of communication and laying out specific areas of anxiety and concern on both sides. Just the act and the fact of greater clarity and understanding is an important signal. We are able in some of these deliberations to dispel some mistaken views about the United States. And China perhaps seeks to do the same with us.

We believe that a more predictable, judicious set of interactions across a variety of spheres is in our best interests, both diplomatic and financial, and hopefully at some point on the military side. Those discussions can be stabilizing. They can create mechanisms for dealing with accidents or miscalculations.

I don’t think they will fundamentally alter the character of the relationship between the United States and China which is essentially competitive — it has been and will be.

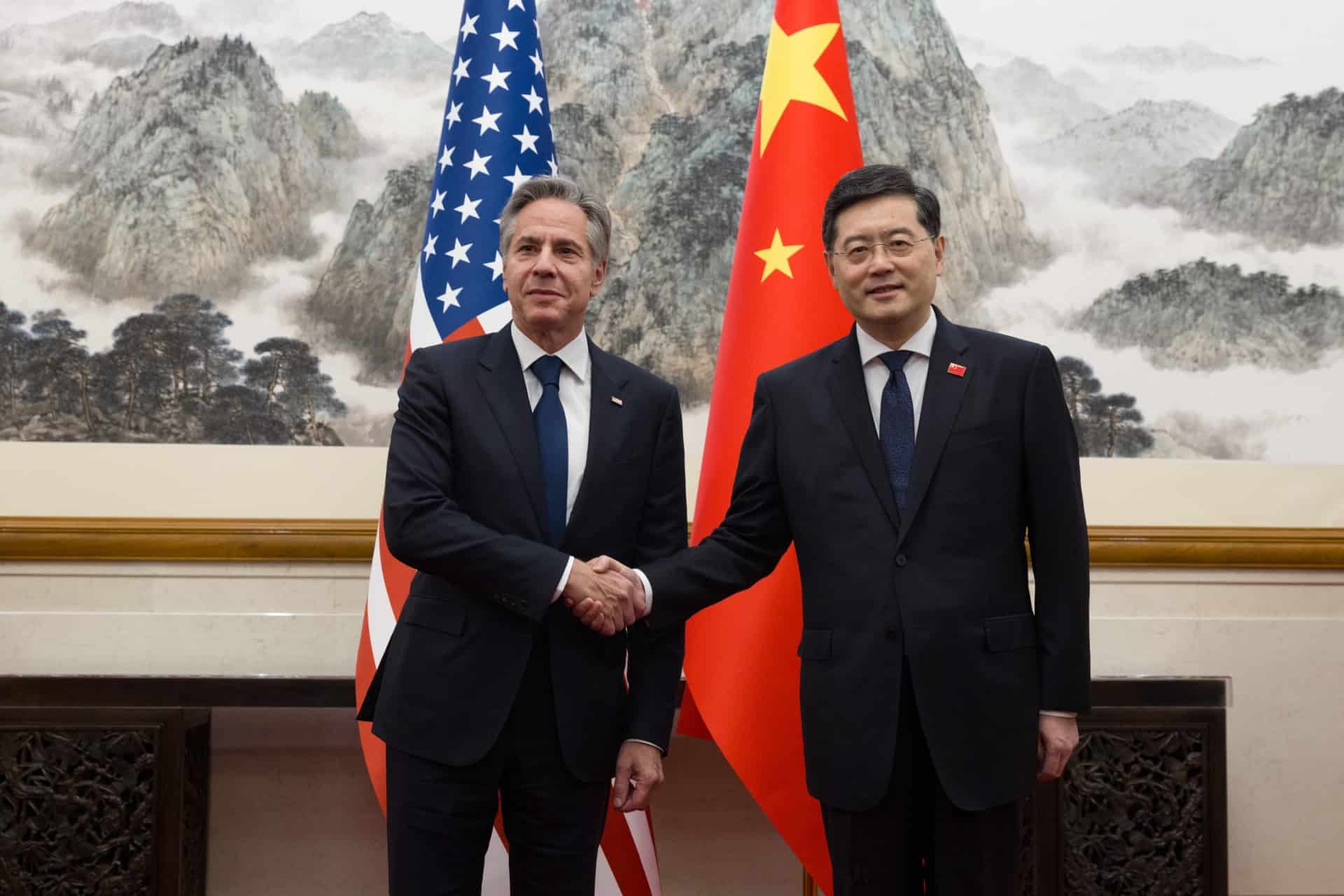

When Secretary of State Blinken went to China, he didn’t get agreement on military-to-military communications — the ‘red phone’ communications the U.S. wanted. They seem to be more open to discussions on the economic side. Are they signaling that what they really care about is the economy?

I first started working on the mil-to-mil relationship between the United States and China in the 1990s. I helped negotiate the maritime agreement between our two countries. We have a series of mechanisms we have established. The challenge has been that China has chosen generally not to use them for a whole host of reasons.

They believe that some of these mechanisms will provide, as they think about it, a seat belt to a speeder. They are worried they will give us greater confidence to operate up close to Chinese territory. But, at the same time, they tend to miscalculate. They would never have thought you might need one of these mechanisms to deal with an errant spy balloon that goes across the United States. There was no mechanism to have that kind of discussion during a completely unplanned or hard-to-imagine event.

The reasons for that ambivalence are not new. It has to do with civil-military relations, party-military relations in China. It has to do with their theories of deterrence. It has to do with anxieties about what these mechanisms might be used for. I wouldn’t indicate that their inhibitions right now are directly related to the state of U.S.-China relations. They’re much more structural than that.

I believe that there are those in the Chinese system who work more on economic issues who still have more ability to maneuver in China. In the security area, the realm for maneuver is very narrow. I don’t deny that there are some that would say, ‘Look, let’s engage Secretary Yellen.’

We are in a period of reviewing what are the best next steps with respect to addressing the still-existing imbalances in the U.S.-China economic relationship.

We have had fulsome discussions at the White House level, at the NSC, at the State Department and the Treasury Department. We will see other actions going forward. This is appropriate and given the current context is about the best that we can do.

In your policy work and writing, you have always recognized a big role for the economy and trade. You have talked about it as a stabilizing influence. To achieve something concrete, wouldn’t it make sense to follow up on the Phase One trade deal and put forward some ideas about tariffs?

I was told that the U.S. has thought twice about cutting tariffs. Once was during the two-year review in January 2022. The Chinese said they would buy more stuff if the U.S. eliminated tariffs. [The U.S. refused.]

Then around July 2022, President Biden talked about cutting tariffs. Yellen was also talking about it. I was told that one reason that didn’t go through is that the Chinese weren’t willing to make reciprocal tariff cuts.

Do you think that this is an area where the U.S. can work with the Chinese?

I’m not going to get into internal deliberations in the government. I believe that the initial steps that Secretary Yellen has taken on macroeconomic dialogues — discussions about the broader global economy and the role of the United States and China — are important. We’ll see what’s possible in terms of next steps.

I would say that across the board, there are generalized concerns about Chinese activities in almost every arena of trade, whether it’s subsidies or forced IP [intellectual property] or technology transfer. That broader reassessment has led to some substantial concerns. We are in a period of reviewing what are the best next steps with respect to addressing the still-existing imbalances in the U.S.-China economic relationship.

I would say that many of the agreements that were made in the Trump administration about substantially boosting Chinese purchases of machine goods, agriculture [and other goods] — most of those did not come to pass. Some of that lack of ambition on the Chinese side has obviously influenced our thinking.

There are a number of reasons why the Chinese didn’t buy what they said they would buy. First, the pledges were unrealistic. Second, there was Covid. Also, I think they thought it would give them leverage. ‘You want us to buy more? Do something in return.’ [Trump trade representative] Robert Lighthizer just came out with a book where he says, other than in purchases, the Chinese have largely lived up to the promises they made.

I understand the U.S. still has plenty of complaints. Isn’t this an area where the two sides could discuss what to do without a lot of emotional baggage?

I don’t really have very much more to offer on this other than to say I believe we will have subsequent economic engagement, not only with Secretary Yellen and some of her team, but with the Commerce Department and others. I believe that these discussions are important. In them, we lay out our concerns. I don’t think we’re ruling out any outcomes in terms of the way forward.

But I will simply say that the general sense is that the actions undertaken by Beijing within the larger context of the world trade system have been antithetical to many of our partners and the United States. They are probably increasing in intensity and tenacity in ways that are concerning.

The basic definition of trade and commerce is meant to be something of mutual benefit. But increasingly what we see is a state ideology that is about seeking advantage in almost every area of encounter. That’s a difficult reality to grasp and to develop a counter strategy to deal with, but that’s exactly what we’re trying to do.

In the Obama administration, you were involved with the Strategic and Economic Dialogues. Now you are talking about increased communication. What did you learn from that experience? [In the annual S&ED sessions, a broad range of U.S. and Chinese officials discussed economic and security issues. The meetings were frequently criticized for not producing concrete results.]

The S&EDs are sometimes caricatured as giant back-and-forths. There were some useful interactions undertaken through that venue. But that doesn’t account for the changes that have taken place in Beijing since then.

That’s something outside commentators perhaps were slow to understand but now probably more fully appreciate — the centralization of power and the role Xi Jinping has taken in unraveling decades of mechanisms of collective leadership. Virtually every major decision is taken by him and a small group around him.

The people that tend to dominate decision making are very, very much influenced by security [issues], both external and internal, much more so than in earlier periods. Then economic and other issues tended to have substantial sway. So we have to make sure that our venues of engagement are appropriate for some of the changes that we’ve seen in China.

What we have seen is this quite dramatic centralization and hierarchy in the Chinese system. To really make changes on any issue, whether it’s on fentanyl or maritime patrols or trade policy, requires an extremely high level of engagement. That’s what we’ve sought to do.

Now with China’s interlocutors, there’s a very narrow scope for discussion. There’s a lot of reciting of talking points. Many times, when we sit across the table from a delegation you get a sense that people are talking for their own team as much as for us. That’s a substantial change, and we need to be attentive to that.

In some respects, it harkens back to an earlier era in China, where ideology and the [party] line were of paramount importance. I have friends in China, some of whom have been partners diplomatically for 30 or 40 years. The conversations we have now are almost unrecognizable from the ones I had 10 or 15 years ago.

Because they are less candid?

Much less candid. Much less able to discuss things.

I’m not going to say who this person is, but I will tell you about an encounter I had not long ago with someone I would consider a very close friend, but also a very effective diplomat. We were talking. We were out on a stroll. I asked him some questions and he stopped me and said, ‘You know, Kurt, I can talk about children. I can talk about grandchildren. We can talk about sports. But some of the discussions that we had before, we can’t have those again.’

This is a very challenging period. It means that every encounter has to be carefully prepared. We need a sense of what we want to accomplish and a careful approach. We have to make clear that we’re not a wildly ardent suitor. We are seeking these engagements because as a great power we have been in situations like this before and in many respects, China is new to some of them. They are frankly coming up to speed in a number of areas.

We still believe that some of their military practices are provocative and dangerous. And we are trying to communicate that clearly, not only in a bilateral context, but multilateral as well.

You were with National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan when he met with China’s top foreign policy official Wang Yi in Vienna in May. What was your takeaway from that meeting?

I thought it was a very useful session. I don’t think they anticipated the effectiveness of some of the things that we’ve done. They’ve had to reckon with that. And I also think they recognize that we have common business.

We tried to talk with him about a number of things and explain our rationale for AUKUS [a joint security agreement between the U.S., U.K. and Australia] and for the Quad [the U.S., Japan, India and Australia]. They lodged their complaints. But at the same time we have sought to be as transparent as we can about our initiatives and why we’re doing what we’re doing.

I wanted to go back to the S&ED for a second. If I understand what you’re saying, the idea of the S&ED was to have lots of communications among various levels of the Chinese government. That’s because it was important to meet different people in different ministries at different levels. Now you’re saying that is less important?

What I would say is that we believe at this juncture, the critical effort in front of us is ensuring that there is a higher degree of effective, systemic communication between the leadership of our two countries. That’s to deal with misconceptions, to establish mechanisms to deal with inadvertence, and to create a higher degree of predictability and hopefully avoid the kinds of surprises that could trigger a crisis.

Our goals remain the same as previous administrations. We intend to maintain peace and stability across the Taiwan Strait… We also have sought to make clear that other countries share an interest in the maintenance of peace and stability.

The last administration, for all its vaunted hawkishness, didn’t move very far on Taiwan. Trump himself basically didn’t care about Taiwan. After Covid, he let his more hawkish people make the moves that they did. But when your administration came in, it was as if you felt that there was almost an imminent threat [of invasion].

During these interviews, I talked with George H.W. Bush’s National Security Advisor Steve Hadley, who told me that in 2008, when the Chinese were worried about the DPP candidate in Taiwan declaring independence, Hu Jintao ordered his military to get prepared militarily when it comes to Taiwan. [U.S. intelligence has picked up that Xi Jinping has issued a similar order.]

Why isn’t an alternative interpretation that any time China worries about a presidential candidate who might declare independence, that they alert their military to get prepared to act?

I would caution you about making a comparison with the 2007-2008 period. There was a very different Chinese leadership then compared to what we’ve since seen since President Xi has come to office. One of the challenges is a lack of a careful study of much of what Xi Jinping has written. He is among the most clear, published, and straightforward [leaders] about his ambitions and his goals.

They involve statements about creating dominance over the United States in technology, long before we discussed these issues. He has laid out clearly, both in internal documents and external statements, the need for China to take massive rapid steps to prepare for potential military scenarios.

Yes, there was a careful buildup during the Hu Jintao period, but that has been accelerated since. We believe that President Xi has exhibited a degree of impatience and ambition with respect to Taiwan that concerns us.

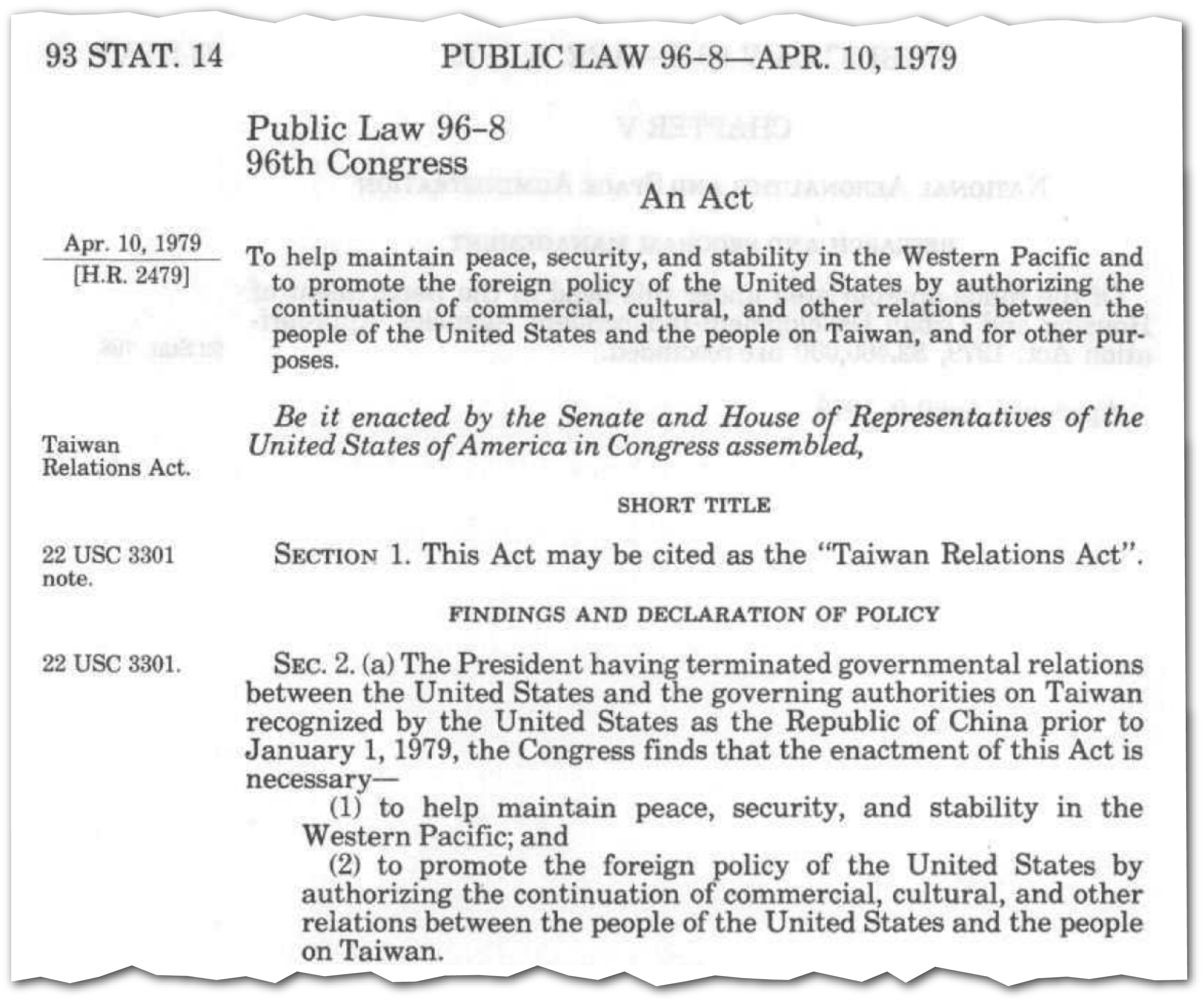

Our goals remain the same as previous administrations. We intend to maintain peace and stability across the Taiwan Strait. We are trying to do that through a number of ways. As the Taiwan Relations Act insists, we maintain our own capability, and we’re investing in it and we have new capacities to show for that. That is the foundational piece of the 1979 Taiwan Relations Act of which then Senator Biden was as signatory. [Under the TRA, the U.S. commits to providing Taiwan with the weaponry necessary to defend itself and resist coercion.]

We also have sought to make clear that other countries share an interest in the maintenance of peace and stability. For the first time, a host of institutions and nations have spoken out about its importance. You’ve seen that in the G7 statement, in the US-ASEAN statement, and in many other bilateral engagements with the Philippines, Japan and the like.

We’ve also taken important steps, again as instructed by the Taiwan Relations Act, to make sure that Taiwan has effective defensive capabilities to be able to meet potential challenges. And we have been very clear with China about steps that they have taken that we believe are provocative and unproductive.

My critique with what you have suggested is that you haven’t appreciated that Xi Jinping is a different kind of leader than previous leaders. You can say this is because of more capability on the part of China. I would say it’s something more than that. If you look at the Chinese buildup — which began in a fundamental way in 1996 and 1997 after the Taiwan crisis of 1994 and 1995 — it is the largest military buildup in history by far. [During these crises, the U.S. sailed aircraft carrier groups through and near the Taiwan Strait.]

Is that because China started from such a low point?

No. I would say not. Look, by most measures we are still the most capable military. But in terms of the number of ships and increasing capabilities, they have made a judgment that after maintaining a minimal deterrent for decades, they are going to have a massive increase in spending on nuclear [and other areas].

It’s not surprising that these investments and their ideological and harsh commentary about security have stoked anxiety in the region. Look at the other major countries of Asia — Australia, South Korea, Japan, India, and other countries in Southeast Asia.

Japan has had a constitution which essentially limits its military investments and its general attitude towards security for 75 years. Largely because of the changing security circumstances, the current Japanese government has decided to do a substantial new set of investments. We have had an unprecedented set of interactions between the United States and South Korea. You’ve seen the increased tension and anxiety along the line of actual control between India and China.

I would also point out to you that the place where we have seen the most substantial change in views about the Indo-Pacific is in Europe, with many European countries understanding the nature of the interconnectedness between the Indo-Pacific and Europe.

And I also remember talking to you about this before, and you had a lot of skepticism that China would associate itself with Russia. And I’m just going to say that was wrong.

Yeah, that was definitely wrong. I thought, why would China throw itself in with essentially an oil state and risk alienating countries that have made it rich through trade and investment? Why do you think China has moved in the way it has with regards to Russia?

It’s a complex question. Some would make the argument that somehow the United States has thrust China into Russia’s arms. I would just reject that out of hand.

The most important project that Xi Jinping has, other than nation building and the singularity of his power, is to build a deeper relationship with Russia. We’re talking about a relationship between two individuals [Putin and Xi]. We’re now up to almost 50 meetings — hundreds and hundreds of hours — and a deep ideological identification of mutual concerns. At the core of that is a desire to check American power.

It’s possible that China believed that if Russia moved quickly and achieved its goals in Ukraine, that a chastened Europe would just remain quiet. It’s possible that they believe that the core of a European identity is commercial pursuits. But whatever their calculations were, they miscalculated. They have misunderstood the essential character of Europe.

Of course, countries still want an economic relationship with China. But [Europeans] find many actions that China has undertaken in Russia with respect to Ukraine to be deeply concerning. They will not say it as directly as the United States, but I can assure you in private conversation, they are surprised, concerned and deeply worried. That is why increasingly in European councils, one of the most important arenas of dialogue is about the Indo-Pacific.

There is a difference between now and an earlier period when we were focusing more on Asia — we called it the pivot [during the Obama administration]. Then — and I have to take some responsibility for this — there was the idea that we were pivoting away from Europe and focusing more on the Indo-Pacific. That was a mistake. Everything that the United States has ever done of purpose on the global stage we have done with Europe.

Probably my most intensive efforts in diplomacy are not just with Asian partners but with European partners. We are having deep discussions not just about China, but about ASEAN, about India, about northeast Asia. Each of these countries want a deeper relationship in the Indo-Pacific. They understand that the lion’s share of the history of the 21st century is likely to be written there. They want to work more constructively there. They want to work with us there. And they are concerned by what they’ve seen.

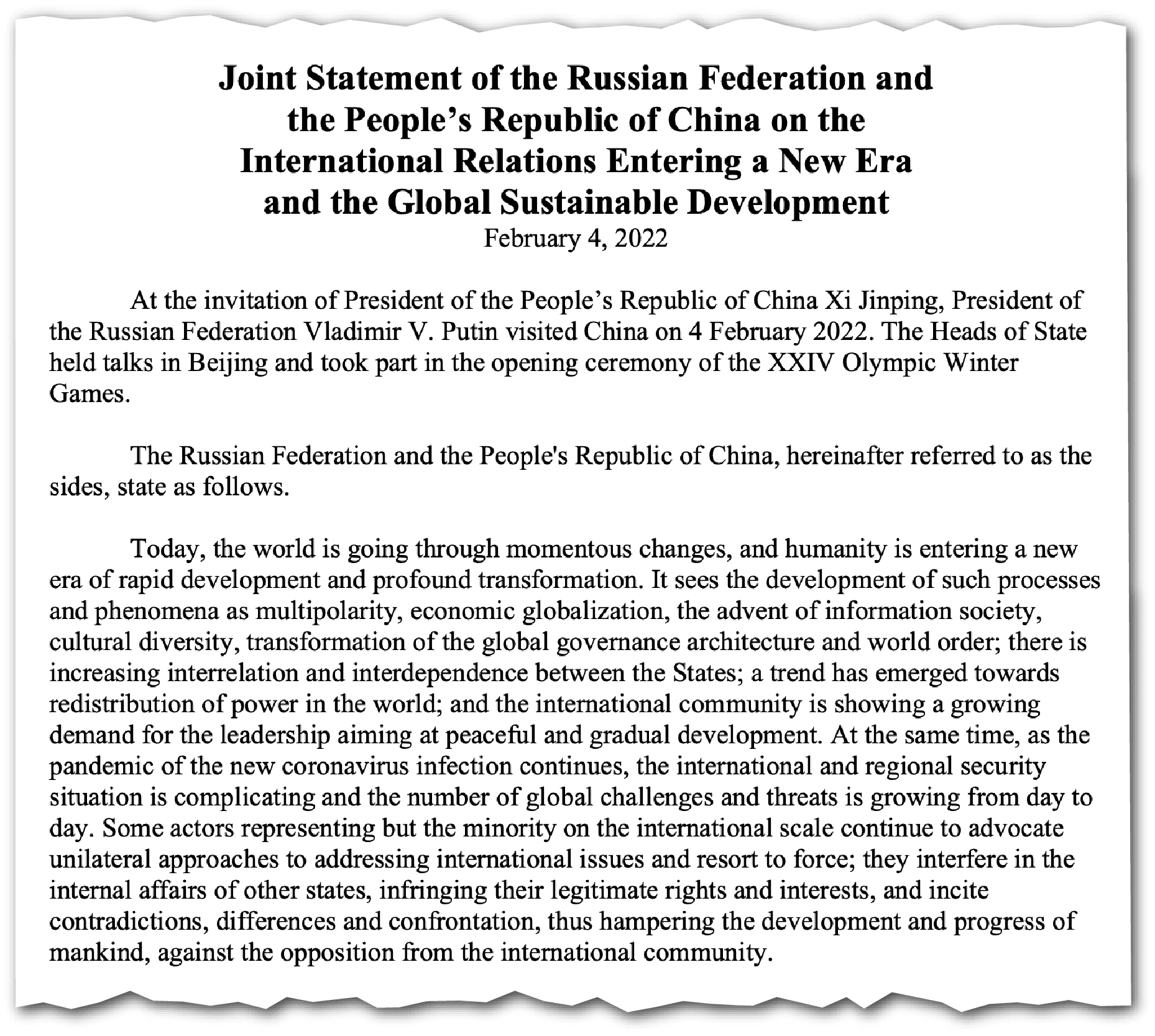

Take a look at the document that China and Russia unveiled a couple of weeks before the invasion if you have any doubts about a sense of imperial purpose. That document, and others like it, represent beliefs and sentiments that are antithetical to ours.

We have tried to be very careful with China about Russia. We’ve told them that if they take specific steps that we would hold them to account. We’ve followed up on that extensively. They have continued many areas of engagement with Russia. They’ve tried to support Russia. In fact, if anything, they’ve intensified their financial, oil and other kinds of relationships since the beginning of the invasion. They have tried to walk this awkward line of explaining to Europe that they are indifferent or not taking sides when they’re clearly taking sides.

The document you’re referring to is the one that talks of a partnership “without limits.”

This is a 24- or 25-page document. Unbelievably detailed with a list of grievances and a world view that people should take a look at.

I found it also written in incredibly turgid communist rhetoric.

When you talk to any businessman or anyone who’s worked with China for a long period, they’ll say, ‘Look, these are practical people. They’re going to make practical solutions and decisions.’

I find increasingly in many of my interactions, that the ideological factor figures prominently. Some of the rhetoric and some of the approaches appear more out of the 1950s and ‘60s, than the aughts and ‘20s.

How has the shadow of the Russia-Ukraine war affected U.S.-China relations? Is part of the reason they’re a bit more open to dialogue because of their concerns that things are going poorly?

Potentially. One of the big reasons they want to have a dialogue is to know what we think about Russia. They were unnerved by what happened two weekends ago in Moscow. [Yevgeny Prigozhin, leader of the Wagner Group, marched with his troops toward Moscow in what has been characterized as a mutiny.]

In all these discussions, whether it’s confidence building, or the economy, or issues associated with Ukrainian diplomacy, there is substantial distrust. It will take time on both sides.

I don’t need to tell you about the complex Chinese psychology about warlords. They have their own experiences of a warlord who got close to an emperor and basically toppled an existing order in China for 100 years. In Chinese councils of power, this has been deeply unnerving. [In response to a follow-up question Campbell said he was referring to the An Lushan Rebellion, which destabilized the Tang dynasty. In 755, An Lushan, a military leader, sought to seize power and set off generations of battles between warlords.]

What we’ve tried to communicate to China directly is that much of this instability — global inflation, challenges to prudent leadership, horrible refugee flows — is a consequence of a horribly implemented war, [one that is] misguided and illegal. And that this war needs to end under terms that are acceptable to Ukraine and others in Europe sooner rather than later. It will not be solved on the battlefield.

China has a role to play. Its most important role, as really Russia’s sole remaining partner and friend, is to encourage them to come to the realization that time is not on their side. The idea that somehow this war will follow the path of the Second World War, where there was terrible Soviet performance at the outset but over time they regained capacity and surged into German territory — I don’t think there’s anything currently in the Russian makeup of forces or conduct of operations that should give anyone that confidence.

If anything, their capacities have been severely tested, and are frankly at risk. The reason why Prigozhin and his troops were able to get so close to Moscow is that the internal security capacity in Russia has been dramatically eroded. So many of those capacities have been needed on the front. We’ve tried to communicate directly with China, that they should use their good offices quietly to get Russia to reevaluate and to withdraw and to seek a peaceful solution

Do you see any impact?

In all these discussions, whether it’s confidence building, or the economy, or issues associated with Ukrainian diplomacy, there is substantial distrust. It will take time on both sides.

One of the most important steps you have taken is the creation of AUKUS. But a skeptic could say, OK, you put some more subs in the water. What do you think is the greater significance?

It creates much greater interoperability, much greater focus among the United States, Great Britain, and Australia. It brings Great Britain more into the Indo-Pacific in common purpose. My own view is that if you have more countries aligned with you in common purpose, that can have a stabilizing, deterrent effort. Those steps also give other countries confidence to be able to speak out and assert their own national security interests.

And it’s not just going to be submarines. It will also involve certain areas of cutting-edge technologies, whether it’s hypersonics, AI, issues associated with anti-submarine warfare and the like. We will work with other countries, including Great Britain and Australia, in a common pursuit. This larger web of engagement is in our best interest.

The effort started with a controversy regarding France. Do you think France might be involved in some of these other efforts? [Australia scrapped its plans to buy submarines from France after the U.S., Australia and Britain announced a deal to equip Australia with nuclear-powered submarines.]

We’re closely associated with France in many things. The door is always open to France to participate. Sometimes they choose to do so; sometimes they don’t. Their preference right now is to work in a more bilateral context with Australia on issues in the-Indo Pacific and we support them.

And what about the Quad? India as a partner has always been disappointing.

I could not disagree more. If you ask me what is the most important bilateral relationship for the United States going forward? I believe India is that country.

More than China?

In terms of establishing a partnership and working on arenas of collaboration in a like-minded way, yes, I think India meets that match. China is important, but important in different ways. I said partnership. I believe that’s what’s critical.

What India offers is deeply significant in terms of technology, the diaspora, educational opportunities, and its desire to play a larger role in the global stage. I’ve only been in government this time for three years. Even during that period, I have seen India’s confidence, its ambition growing.

Yes, there is some significant distrust between the United States and India. What we see is a longer historical relationship that has been marked a lot by distrust. I see that falling by the wayside. Take a look at what was accomplished at the state visit two weeks ago. That is a clarion call for a much deeper set of strategic engagements.

The issue with India is that they have had some leaders who wanted to make big changes, but were only able to make some moderate changes. But China remade itself in the meantime. It turned itself into the factory floor of the world. India would seem to have the same potential but has never been able to manage it.

What you’re referring to is an India of the ‘90s and 2000s, and I don’t think I can disagree with you. But if you talk to many Indian friends, sometimes they will say, ‘Look, I might have some issues with certain elements of government policy, but I see India on the move. I see steps to eliminate corruption, to work on a variety of different areas in technology and education. And yes, I see a very different India today than I saw a decade ago.’

You started working on China in the Clinton administration, an administration that was entirely focused on engagement. Yet by 2018, in Foreign Affairs, you declared engagement was a failure. By 2021 you said the era of engagement had ended. Aren’t we back to an effort to try to restart engagement?

The drama of Asia is in the nuance, not in the starkness. During the Obama administration, we practiced a combination of certain kinds of engagements and deterrence. It was a carefully orchestrated mix of actions. I don’t think it’s that dissimilar now, only that the elements associated with the efforts to contest China are more important.

One of the most interesting questions about U.S.-China relations is why it took so long for the United States to recognize that they were dealing with a competitor that was seeking to undermine it in many ways.

Of course, we’re going to continue to engage. But the broader period that was described as engagement was one in which people had overly ambitious goals for how Chinese society would change and evolve. Some of those assumptions have been discarded. There’s a recognition that we were overly ambitious about what we thought we could achieve with respect to the trajectory of where China was going.

We over-invested in the Middle East and south Asia. We missed the dominant drumbeat of global politics beating in Asia. We were late to that. We were probably too wedded to a kind of commercial engagement, and we did not see some of the gathering clouds — or chose not to.

We don’t seek the toppling of the Chinese regime… We are also aware that elements of this global operating system are under threat. We’re seeking to stabilize, defend and secure it.

What you have seen in recent times is a clear-headed assessment that, yes, we need to continue to have a relationship with China. But some of the things that China is doing require a consequential set of actions to push back.

One last question. Treasury secretary after Treasury secretary has said that a strong and prosperous China is in the U.S. interest. Do you think that’s still the case?

I would answer it this way. We don’t seek the toppling of the Chinese regime. We are seeking to contest [China] in a number of ways. We’re trying to increase our own capacity — our own ability to compete. We’re trying to create a degree of redundancy across the board. We are also aware that elements of this global operating system are under threat. We’re seeking to stabilize, defend and secure it.

The way you posed the question is too narrow and bilateral. Our goals really have more to do with the larger world. I do believe as part of that we can have a healthy, competitive relationship. That will be difficult to establish; I acknowledge that. But at the same time, we also believe in taking steps to secure the allied and partner capacity we think is going to be essential.

Bob Davis, a former correspondent at The Wall Street Journal, covered U.S.-China relations beginning in the 1990s. He co-authored “Superpower Showdown,” with Lingling Wei, which chronicles the two nations’ economic and trade rivalry. He can be reached via bobdavisreports.com.